In my studies of the development of Japanese music from the Heian Period to the present, I observed a rich and complex evolution influenced by cultural, political, and technological changes in the region, a finding that others have likely noted as well. I also see a notable difference compared to Western developments: the evolution of Japanese music appears to be much more extensive. I hope you find the development just as fascinating as I do.

Heian Period (794-1185)

During the Heian period (794-1185), Japanese music was profoundly influenced by the cultural and political milieu of the time, characterized by the flourishing of courtly arts and the importation of musical forms from China and Korea. The primary musical form of this period was Gagaku, which can be divided into two main categories: instrumental music and vocal music. Here are the key aspects of Japanese music in the Heian period:

Gagaku (雅楽)

Gagaku, meaning “elegant music,” is the oldest surviving form of orchestral music in Japan and was performed at the imperial court and at religious ceremonies. Gagaku itself is divided into two main types: Kangen (instrumental music) and Bugaku (dance music).

Kangen (管弦)

- Instrumental Music: Kangen was purely instrumental and performed as background music or as a standalone performance. It included a variety of instruments such as:

- Wind Instruments: Shō (mouth organ), hichiriki (double-reed instrument), and ryuteki (transverse flute).

- String Instruments: Biwa (lute) and koto (zither).

- Percussion Instruments: Kakko (small drum), taiko (large drum), and shōko (small gong).

Bugaku (舞楽)

- Dance Music: Bugaku included choreographed dances accompanied by the gagaku orchestra. The dances often depicted stories or represented various deities and mythical creatures. There are two main types of bugaku:

- Saho-no-mai: Dances from the left, often of Chinese origin.

- Uho-no-mai: Dances from the right, often of Korean or Manchurian origin.

Vocal Music

- Shōmyō (声明): Buddhist chanting performed by monks, which played a significant role in religious ceremonies. Shōmyō involved intricate vocal techniques and was performed without instrumental accompaniment.

- Saibara (催馬楽) and Rōei (朗詠): These were vocal forms with instrumental accompaniment that were performed at court. Saibara were folk songs adapted for court use, while Rōei were Chinese poems set to music.

Key Characteristics

- Formal and Structured: Gagaku music was highly formalized, with strict rules governing its performance. The music was often slow and meditative, reflecting the aesthetic preferences of the court.

- Symbolic and Ceremonial: Music played a crucial role in court ceremonies, rituals, and religious observances. It was seen as a means to connect with the divine and uphold the social order.

- Imported Influences: Gagaku was heavily influenced by the music of China and Korea, reflecting the cultural exchanges of the time. The Japanese adapted these foreign elements to create a distinct style that became a symbol of imperial power and sophistication.

Preservation and Transmission

- Imperial Court: The imperial court was the center of musical activity, where musicians were trained and performances were held. The court maintained a detailed record of musical works and performances.

- Shinto Shrines and Buddhist Temples: Music was also an integral part of religious practices, and temples and shrines played a role in preserving musical traditions.

Overall, the Heian period was a time of significant development and refinement in Japanese music, laying the foundation for many musical traditions that would continue to evolve in subsequent periods.

Kamakura Period (1185-1333)

The Kamakura period (1185-1333) was a time of significant political and social change in Japan, marked by the establishment of the Kamakura shogunate and the rise of the samurai class. This period also saw important developments in Japanese music, with a continued influence of earlier traditions and the emergence of new forms and practices. Here are the key aspects of Japanese music during the Kamakura period:

Buddhist Chanting (Shōmyō)

- Shōmyō (声明): Buddhist chanting remained highly significant during the Kamakura period. The spread of new Buddhist sects, such as Pure Land Buddhism (Jōdo-shū) and Zen Buddhism, led to a diversification in the styles and practices of shōmyō. These chants were performed during religious ceremonies and were an integral part of temple life.

Gagaku and Bugaku

- Gagaku (雅楽): Although Gagaku, the classical court music, began to decline in prominence as the political power shifted from the imperial court in Kyoto to the military government in Kamakura, it still played a role in court ceremonies and religious festivals.

- Bugaku (舞楽): The dance component of Gagaku, performed at court and shrines, continued to be practiced, though its prevalence decreased with the decline of courtly culture.

Noh Theater

- Noh (能): The foundations of Noh theater were laid during the Kamakura period. Although it reached its full development in the subsequent Muromachi period, the early forms of Noh, influenced by earlier performing arts such as Dengaku (田楽) and Sarugaku (猿楽), began to take shape. Noh combined elements of dance, drama, and music, featuring the use of flutes and drums to accompany performances.

Heike Biwa

- Heike Biwa (平家琵琶): This was a form of narrative music performed by blind monks called biwa hōshi (琵琶法師). They used the biwa, a type of lute, to accompany their recitations of the “Tale of the Heike” (Heike Monogatari), an epic account of the Genpei War between the Taira and Minamoto clans. This form of storytelling and music played a crucial role in preserving and transmitting historical and cultural narratives.

Popular Music and Folk Traditions

- Imayō (今様): Popular songs of the period, known as Imayō, were sung both at court and among the common people. These songs often reflected contemporary themes and were sometimes accompanied by instruments like the koto or biwa.

- Dengaku (田楽): Originally a form of rural entertainment linked to rice planting rituals, Dengaku evolved into a more sophisticated performing art during the Kamakura period. It involved music, dance, and acrobatics and was performed at various festivals and celebrations.

Key Instruments

- Biwa (琵琶): A short-necked wooden lute used in various forms of narrative music and court performances.

- Koto (琴): A long zither with movable bridges used in court music and later adapted for solo and ensemble performances.

- Shō (笙): A mouth organ used in Gagaku and other court music.

- Hichiriki (篳篥): A double-reed instrument used in Gagaku.

Cultural Context

- Decline of Court Culture: The shift in political power from the imperial court to the military shogunate in Kamakura led to a decline in the prominence of court music traditions like Gagaku. However, religious music and folk traditions continued to thrive and evolve.

- Rise of the Samurai Class: The samurai class became more influential, and their patronage of the arts, including music, began to shape cultural developments. This shift influenced the thematic content of musical performances, often reflecting the values and stories of the warrior class.

In summary, the Kamakura period was a time of both continuity and change in Japanese music. While some traditional forms persisted, new influences and practices emerged, reflecting the broader social and political transformations of the era.

Muromachi Period (1336-1573)

The Muromachi period (1336-1573), also known as the Ashikaga period, was marked by political instability, cultural flowering, and the establishment of new artistic and musical forms. Here are the key aspects of Japanese music during this period:

Noh Theater

- Development of Noh (能): Noh theater, which had its roots in the Kamakura period, reached its full development during the Muromachi period. It became a sophisticated form of musical drama, combining elements of dance, music, and acting. Noh performances were characterized by their slow, deliberate movements and symbolic gestures.

- Instruments: The music in Noh was provided by a small ensemble called the hayashi, consisting of the nohkan (a bamboo flute) and three types of drums: ko-tsuzumi (small hand drum), ō-tsuzumi (large hand drum), and taiko (stick drum). The chorus (jiutai) provided vocal accompaniment, enhancing the narrative and emotional impact of the performance.

Kōwaka-mai

- Kōwaka-mai (幸若舞): This form of musical storytelling combined elements of dance and recitation, often recounting historical and legendary tales. It was performed to the accompaniment of instruments like the biwa and was popular among the samurai class.

Heike Biwa

- Heike Biwa (平家琵琶): The tradition of reciting the “Tale of the Heike” continued, with blind biwa hōshi (琵琶法師) performing the epic narratives to the accompaniment of the biwa. This form of music remained important in preserving and transmitting historical stories and cultural values.

Gagaku and Bugaku

- Continued Tradition: Despite the decline in court influence, Gagaku and Bugaku traditions continued to be performed at imperial and religious ceremonies. These classical forms of music and dance were maintained by the court and shrines, preserving their ancient roots.

Zen Buddhism and Musical Influence

- Shakuhachi (尺八): The bamboo flute, shakuhachi, became closely associated with Zen Buddhism during this period. It was played by wandering Zen monks, known as komusō (虚無僧), as a form of meditation and spiritual practice. The shakuhachi’s haunting and meditative sound reflected the Zen aesthetic of simplicity and introspection.

- Sōkyoku (筝曲): Music for the koto, or sōkyoku, also saw development during the Muromachi period. While initially associated with court music, the koto began to be used in more secular and folk contexts.

Popular and Folk Music

- Dengaku (田楽): Dengaku, originally linked to agricultural rituals, continued to evolve as a form of entertainment, incorporating music, dance, and acrobatics. It was performed at festivals and gatherings, reflecting the lively folk culture of the period.

- Sarugaku (猿楽): Sarugaku, which included comedic skits and acrobatics, was a precursor to Noh theater. It remained popular among the common people and influenced the development of more formal theatrical traditions.

Key Instruments

- Biwa (琵琶): Used in narrative music and court performances.

- Koto (琴): Played in both court and more secular settings.

- Shō (笙): A mouth organ used in Gagaku.

- Hichiriki (篳篥): A double-reed instrument used in Gagaku.

- Shakuhachi (尺八): A bamboo flute associated with Zen monks and meditation.

Cultural Context

- Rise of the Ashikaga Shogunate: The Ashikaga shogunate, based in Kyoto, provided patronage to the arts, including music. This support helped preserve traditional forms while encouraging new artistic expressions.

- Cultural Synthesis: The Muromachi period was a time of cultural synthesis, blending indigenous Japanese traditions with influences from China and Korea. This period saw the flourishing of the arts, including the tea ceremony, ink painting, and garden design, which were often accompanied by music.

In summary, the Muromachi period was a time of significant cultural development in Japanese music. Traditional forms were preserved and refined, while new forms emerged, reflecting the dynamic and evolving cultural landscape of the era.

Azuchi-Momoyama Period (1573-1603)

The Azuchi-Momoyama period (1573-1603) was a time of political consolidation and cultural flourishing in Japan, marked by the unification efforts of powerful daimyos such as Oda Nobunaga, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, and later Tokugawa Ieyasu. This period saw significant developments in Japanese music, influenced by both native traditions and increasing contact with foreign cultures. Here are the key aspects of Japanese music during the Azuchi-Momoyama period:

Noh Theater

- Continued Flourishing of Noh: Noh theater, which had reached maturity during the Muromachi period, continued to thrive under the patronage of the samurai class. The structured, ceremonial nature of Noh suited the tastes of the military elite, and performances were often held at castles and during important events.

- Instruments and Performance: The musical ensemble for Noh (hayashi) remained the same, with the nohkan (flute), ko-tsuzumi (small hand drum), ō-tsuzumi (large hand drum), and taiko (stick drum) providing the accompaniment, alongside a chorus (jiutai).

Kabuki

- Early Development of Kabuki: The origins of Kabuki theater can be traced back to this period, particularly with the performances of Okuni, a shrine maiden who began staging dances and skits in Kyoto around 1603. These performances combined dance, drama, and music, laying the groundwork for what would become a major theatrical form in the Edo period.

Bunraku

- Roots of Bunraku: Puppet theater, which later evolved into Bunraku, began to take shape during the Azuchi-Momoyama period. Puppeteers performed dramatic narratives with the accompaniment of music, primarily using the shamisen, a three-stringed instrument that became central to the genre.

Introduction of Western Music

- Contact with Europeans: The arrival of Portuguese and Spanish missionaries and traders brought Western musical instruments and styles to Japan. The introduction of instruments such as the harpsichord, violin, and guitar influenced Japanese music, particularly in the coastal trading ports.

- Christian Hymns: Jesuit missionaries introduced Christian hymns, which were sometimes sung in Japanese and used Western musical notation. These hymns influenced the local music and led to the creation of hybrid musical forms.

Gagaku and Court Music

- Continuation of Gagaku: Despite the political upheaval and the shift in power away from the imperial court, Gagaku music continued to be performed, maintaining its status as an important cultural tradition. The court and major temples and shrines preserved these ancient musical forms.

Popular and Folk Music

- Biwa Hōshi and Heike Biwa: The tradition of biwa hōshi (blind biwa players) reciting the “Tale of the Heike” persisted, with performances being popular among both the samurai class and common people.

- Zokkyoku (俗曲): Popular songs and folk music, known as zokkyoku, were performed by traveling musicians. These songs often reflected everyday life, social issues, and historical events, providing entertainment and storytelling.

Key Instruments

- Shamisen (三味線): The shamisen, introduced in the late Muromachi period, became increasingly popular during the Azuchi-Momoyama period. It was used in various forms of music, including Kabuki and Bunraku.

- Biwa (琵琶): Continued to be used in narrative music and by biwa hōshi.

- Koto (琴): The koto maintained its role in both court music and popular music.

- Fue (笛): Flutes, including the nohkan used in Noh theater, continued to be important.

- Taiko (太鼓): Various types of drums were used in theatrical and ceremonial contexts.

Cultural Context

- Patronage of the Arts: The powerful daimyos of the Azuchi-Momoyama period were great patrons of the arts, using cultural projects to display their power and sophistication. This patronage helped to sustain and develop various musical forms.

- Cultural Exchange: Increased contact with foreign traders and missionaries led to cultural exchange, influencing Japanese music and introducing new instruments and styles.

In summary, the Azuchi-Momoyama period was a dynamic era for Japanese music, marked by the preservation and refinement of traditional forms, the early development of new theatrical genres, and the introduction of Western musical influences. This period set the stage for further musical evolution in the subsequent Edo period.

Edo Period (1603-1868)

The Edo period (1603-1868), also known as the Tokugawa period, was a time of relative peace, political stability, and cultural development in Japan. The Tokugawa shogunate’s policies of isolation (sakoku) and strict social hierarchy profoundly influenced all aspects of Japanese life, including music. Here are the key aspects of Japanese music during the Edo period:

Kabuki Theater

- Kabuki (歌舞伎): Kabuki theater evolved into a major form of entertainment during the Edo period, characterized by its lively performances, elaborate costumes, and dynamic stagecraft. Music played a crucial role in Kabuki, with the shamisen as the central instrument.

- Nagauta (長唄): A form of music that accompanied Kabuki, featuring shamisen, percussion, and vocal music. It helped set the mood and pace of the performance.

- Gidayū-bushi (義太夫節): A narrative music style used in Kabuki, named after the famous chanter Takemoto Gidayū. It involved dramatic vocalizations accompanied by the shamisen.

Bunraku Puppet Theater

- Bunraku (文楽): Bunraku, or puppet theater, flourished alongside Kabuki. It combined intricate puppetry with the chanting of narratives (joruri) and shamisen music.

- Narration and Shamisen: The tayū (chanter) narrated the story with intense emotion, while the shamisen player provided musical accompaniment, creating a powerful dramatic effect.

Gagaku and Court Music

- Gagaku (雅楽): The classical court music tradition continued to be performed at the imperial court and major Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples, preserving ancient pieces and ceremonial music.

- Bugaku (舞楽): The dance component of Gagaku, featuring traditional dances accompanied by the Gagaku orchestra.

Sankyoku and Chamber Music

- Sankyoku (三曲): This chamber music genre involved three instruments: the koto (zither), shamisen (three-stringed lute), and shakuhachi (bamboo flute). Sankyoku pieces often included vocal parts and were performed by small ensembles.

- Jiuta (地歌): A type of music for the shamisen and voice that often accompanied koto and shakuhachi in sankyoku ensembles.

Shakuhachi Music

- Shakuhachi (尺八): The bamboo flute gained prominence as both a solo instrument and in ensemble settings. It was closely associated with the Fuke sect of Zen Buddhism, whose monks, known as komusō, played the shakuhachi as a form of meditation and religious practice.

- Honkyoku (本曲): The traditional repertoire of solo shakuhachi pieces played by komusō monks, characterized by their meditative and introspective nature.

Folk Music and Popular Songs

- Min’yō (民謡): Traditional folk songs that were passed down orally and varied by region. Min’yō were performed at festivals, celebrations, and during daily work.

- Hauta (端唄) and Kouta (小唄): Short, lyrical songs that were popular in urban areas. They often dealt with themes of love and nature and were typically accompanied by the shamisen.

Religious Music

- Shōmyō (声明): Buddhist chanting continued to play a significant role in religious ceremonies and practices. Different sects of Buddhism had their own styles and repertoires of shōmyō.

- Kagura (神楽): Shinto music and dance performed at shrines, often involving the use of traditional instruments like the kagura-bue (flute) and taiko (drums).

Western Influence

- Rangaku (蘭学) Influence: Despite Japan’s policy of isolation, limited contact with Dutch traders in Nagasaki (Rangaku) led to some exposure to Western music and instruments. However, the overall influence on Japanese music was minimal during this period.

Key Instruments

- Shamisen (三味線): A three-stringed lute used in various musical genres, including Kabuki, Bunraku, and sankyoku.

- Koto (琴): A 13-stringed zither used in court music, sankyoku, and solo performances.

- Shakuhachi (尺八): A bamboo flute associated with Zen Buddhist monks and used in both solo and ensemble music.

- Taiko (太鼓): Various types of drums used in theater, religious ceremonies, and festivals.

- Biwa (琵琶): A short-necked lute used in storytelling and court music.

Cultural Context

- Isolation and Stability: The policy of sakoku limited foreign influence, allowing Japanese music to develop independently and maintain traditional forms.

- Urbanization and Merchant Class: The growth of cities and the rise of the merchant class led to the proliferation of popular entertainment forms, such as Kabuki and Bunraku, and the development of new musical genres.

In summary, the Edo period was a time of rich musical development in Japan, characterized by the flourishing of theater music, the preservation and refinement of classical traditions, and the rise of new popular and folk music forms. This period laid the foundation for many aspects of modern Japanese music.

Meiji Period (1868-1912)

The Meiji period (1868-1912) was a time of profound transformation in Japan, marked by the end of the Tokugawa shogunate, the restoration of imperial rule, and the country’s rapid modernization and Westernization. These changes had significant impacts on Japanese music, leading to the fusion of traditional forms with Western influences and the creation of new musical genres. Here are the key aspects of Japanese music during the Meiji period:

Western Influence and Modernization

- Introduction of Western Music: The Meiji government’s policies of modernization and openness to Western culture led to the widespread introduction of Western music and musical instruments. Military bands, schools, and Western-style concerts became common, and Western music theory and notation were adopted.

- Western Instruments: Instruments such as the piano, violin, and brass instruments were introduced and became popular, particularly in urban areas. The government and educational institutions encouraged learning Western instruments and styles.

Education and Institutional Changes

- Music Education: Western music education was institutionalized with the establishment of music schools and the inclusion of music in the public school curriculum. The Tokyo Music School (now Tokyo University of the Arts) was founded in 1879 to train musicians in Western classical music.

- Military Bands: Western-style military bands were established, and their performances helped popularize Western music among the Japanese public.

Sōkyoku and Traditional Music

- Sōkyoku (筝曲): The traditional music for the koto (zither) continued to be popular, with composers like Michio Miyagi (1894-1956) contributing to its modernization by incorporating Western elements and new techniques.

- Shamisen and Jiuta: The shamisen (three-stringed lute) and jiuta (traditional songs) maintained their presence in Japanese music, although they were influenced by Western musical forms and harmonies.

The Development of New Genres

- Gagaku and Noh: Traditional court music (Gagaku) and Noh theater music were preserved and continued to be performed, but they were also studied and documented more rigorously, leading to a revival and increased appreciation of these classical forms.

- Shingaku (新楽): New compositions that blended Western and Japanese musical elements emerged, creating hybrid genres that reflected the changing cultural landscape.

Popular Music and Enka

- Enka (演歌): Although enka as a distinct genre fully developed in the 20th century, its roots can be traced back to the Meiji period. Enka combined traditional Japanese music with Western influences and often featured sentimental and nostalgic themes.

- Ryūkōka (流行歌): Popular songs that emerged in the Meiji period, influenced by Western melodies and harmonies, paved the way for modern Japanese popular music.

Western Classical Music

- Adoption and Adaptation: Western classical music, including orchestral and chamber music, opera, and choral works, began to be performed and appreciated in Japan. Japanese composers and musicians started studying Western classical music and creating compositions that reflected both Western techniques and Japanese aesthetics.

Key Instruments

- Western Instruments: Piano, violin, cello, and brass instruments.

- Traditional Instruments: Koto (zither), shamisen (three-stringed lute), shakuhachi (bamboo flute), and biwa (lute).

Cultural Context

- Meiji Restoration: The Meiji Restoration led to the modernization and Westernization of Japan, significantly influencing all cultural aspects, including music.

- Industrialization and Urbanization: Rapid industrialization and urbanization created new opportunities for musical performances and education, leading to a more diverse musical landscape.

- Cultural Exchange: Increased contact with the West facilitated cultural exchange, leading to the incorporation of Western musical elements into traditional Japanese music and the creation of new hybrid forms.

In summary, the Meiji period was a transformative era for Japanese music, characterized by the introduction and assimilation of Western music, the modernization of traditional music, and the development of new musical genres. This period set the foundation for the rich and diverse musical traditions that would continue to evolve in the 20th century and beyond.

Taisho Period (1912-1926)

The Taisho period (1912-1926) was a time of continued modernization and cultural blending in Japan. During this era, the influence of Western music grew stronger, traditional forms were reinterpreted, and new genres emerged. Here are the key aspects of Japanese music during the Taisho period:

Western Classical Music

- Adoption and Popularization: Western classical music became more popular and accessible in Japan. Concerts featuring orchestral, chamber, and solo performances were increasingly common, and Western operas were staged.

- Music Education: The study of Western classical music continued to be institutionalized, with the Tokyo Music School (now Tokyo University of the Arts) playing a central role. Many Japanese musicians went abroad to study in Europe and the United States, bringing back new techniques and repertoire.

Western Influence on Traditional Music

- Modernization of Traditional Instruments: Instruments like the koto, shamisen, and shakuhachi were adapted to incorporate Western musical elements. Composers experimented with blending traditional Japanese sounds with Western harmonies and structures.

- Shin Nihon Ongaku (新日本音楽): A movement aimed at creating a new Japanese music by integrating Western techniques with traditional Japanese music. Composers like Michio Miyagi pioneered this approach, composing pieces for traditional instruments that used Western scales and forms.

Popular Music

- Enka and Ryūkōka: The genre of enka continued to evolve, blending traditional Japanese music with Western influences. Ryūkōka, or popular songs, became increasingly significant, laying the foundation for modern Japanese pop music. These songs often featured Western instruments and melodies.

- Jazz and Tango: Western popular music styles like jazz and tango became fashionable in Japan, especially in urban areas. Dance halls and clubs featuring live jazz bands became popular, and Japanese musicians began to play and compose in these styles.

Traditional Genres

- Noh and Kabuki: Traditional theatrical forms like Noh and Kabuki maintained their importance, with performances continuing to attract audiences. However, these forms also faced competition from the rising popularity of Western-influenced entertainment.

- Gagaku: The classical court music of Gagaku was preserved and continued to be performed, though it was increasingly seen as a traditional art form rather than a living musical practice.

New Musical Forms

- Shin Nihon Ongaku (新日本音楽): The movement for new Japanese music led to the creation of pieces that combined traditional Japanese instruments with Western compositional techniques. This period saw a flourishing of such compositions, aiming to create a uniquely Japanese yet modern sound.

- Kōshinkyoku (行進曲): Marching songs and military band music, influenced by Western military traditions, became popular during this period, reflecting Japan’s growing nationalism and modernization of its military forces.

Key Instruments

- Western Instruments: Piano, violin, and other Western classical instruments continued to gain popularity.

- Traditional Instruments: Koto, shamisen, shakuhachi, biwa, and taiko drums remained central to Japanese music, with innovations and adaptations incorporating Western elements.

Cultural Context

- Taisho Democracy: The period was marked by a relative liberalization in politics and culture, known as Taisho Democracy, which encouraged cultural experimentation and the blending of Western and Japanese elements.

- Urbanization and Modernity: Rapid urbanization and the growth of a middle class led to increased leisure activities and the consumption of various forms of entertainment, including music. The cultural life in cities like Tokyo and Osaka was vibrant and diverse.

- Technology and Media: Advances in technology, such as the gramophone and radio, facilitated the spread of both Western and Japanese music to a broader audience. Recordings and broadcasts allowed people to experience new forms of music in their homes.

In summary, the Taisho period was a time of significant cultural blending and innovation in Japanese music. The increasing influence of Western music, the modernization of traditional forms, and the emergence of new genres all contributed to a dynamic and evolving musical landscape. This period set the stage for further developments in the Showa period and beyond.

Early Showa Period (1926-1989)

The Early Showa period (1926-1989) is often divided into the pre-war (1926-1945) and post-war (1945-1989) eras, each with distinct musical developments. This period saw Japan undergo dramatic social, political, and cultural changes, impacting its music scene profoundly.

Pre-War Showa Period (1926-1945)

Western Classical Music

- Orchestras and Composers: Western classical music continued to gain prominence. The NHK Symphony Orchestra, founded in 1926, became a major institution. Japanese composers such as Kosaku Yamada and Akira Ifukube studied Western techniques and composed symphonic works, operas, and ballets.

- Education and Performance: Music education flourished, with conservatories and music schools teaching Western classical music. Public concerts and recitals became popular, fostering a greater appreciation for Western music.

Popular Music

- Ryūkōka: This genre of popular music, blending traditional Japanese and Western elements, continued to evolve. Influences from jazz, tango, and other Western genres were incorporated, leading to new styles.

- Enka: Although fully emerging as a distinct genre later, the roots of enka were being laid, characterized by emotional singing and themes of love and nostalgia.

- Jazz and Dance Music: Jazz became very popular, especially in urban centers like Tokyo and Osaka. Dance halls, jazz clubs, and radio broadcasts spread the genre. Japanese musicians began to perform and record jazz, creating a vibrant jazz scene.

Traditional Music

- Preservation and Adaptation: Traditional music, including Gagaku, Noh, and Kabuki, continued to be performed. Efforts were made to preserve these forms while also experimenting with incorporating Western influences.

- Folk Music: Min’yō (folk songs) remained an important part of cultural life, often performed at festivals and community events.

Military and Patriotic Music

- Nationalism: The rise of nationalism in the 1930s and 1940s led to the production of patriotic and military songs. These were used for propaganda purposes and to boost morale during wartime.

Post-War Showa Period (1945-1989)

Western Classical Music

- Reconstruction and Growth: After World War II, Western classical music continued to flourish. Japanese orchestras, opera companies, and conservatories played a crucial role in the cultural reconstruction.

- Influential Composers: Composers like Toru Takemitsu gained international acclaim. Takemitsu’s work often blended Western avant-garde techniques with Japanese traditional music.

Popular Music

- Kayōkyoku: A genre of Japanese pop music that emerged in the post-war period, characterized by its blend of Western pop and traditional Japanese elements. Artists like Hibari Misora became iconic figures.

- Enka: Fully developed as a genre, enka became immensely popular, reflecting themes of nostalgia and loss. Singers like Hibari Misora and Sayuri Ishikawa were major stars.

- Rock and Roll: The 1950s and 1960s saw the rise of rock and roll, influenced by American and British music. Japanese rock bands like The Spiders and The Tigers gained popularity.

- New Music and City Pop: In the 1970s and 1980s, genres like New Music and City Pop emerged, characterized by sophisticated production and urban themes. Artists like Yumi Matsutoya and Tatsuro Yamashita were influential.

Traditional and Folk Music

- Continued Preservation: Traditional music continued to be preserved and performed, often with government support. Festivals and cultural events played a key role in maintaining these traditions.

- Folk Revival: The 1970s saw a revival of interest in min’yō and traditional folk music, with artists like Takio Ito bringing these forms to new audiences.

Influence of Technology

- Recording Industry: Advances in recording technology and the growth of the music industry allowed for greater dissemination of music. Vinyl records, cassettes, and later CDs became the primary media for music distribution.

- Television and Radio: The rise of television and radio as dominant media brought music to a wider audience. Shows like “The Best Ten” popularized new music and artists.

- Synthesizers and Electronic Music: The introduction of synthesizers and electronic instruments in the 1970s and 1980s led to the development of new sounds and genres, influencing both popular and experimental music.

Key Instruments

- Western Instruments: Piano, violin, and other classical instruments continued to gain popularity.

- Traditional Instruments: Koto, shamisen, shakuhachi, and taiko drums remained central to Japanese music, often used in both traditional and contemporary contexts.

Cultural Context

- Economic Growth: The post-war economic boom allowed for increased consumer spending on entertainment and music.

- Cultural Exchange: Increased contact with the West, both culturally and economically, facilitated the exchange of musical ideas and styles.

- Youth Culture: The emergence of a distinct youth culture in the 1960s and 1970s, influenced by global trends, led to new musical movements and genres.

In summary, the Early Showa period was a time of significant musical evolution in Japan, characterized by the continued influence of Western music, the development of new popular genres, and the preservation and adaptation of traditional music. This period laid the groundwork for the diverse musical landscape that would continue to evolve in the late 20th century and beyond.

Post-World War II

The post-World War II period in Japan (1945 onwards) was marked by profound changes and rapid modernization, impacting all aspects of society, including music. This era saw the rise of new musical genres, the fusion of Western and Japanese elements, and the growth of a vibrant music industry. Here are the key aspects of Japanese music during the post-war period:

Immediate Post-War Era (1945-1950s)

Western Influence and Rebuilding

- Occupation Period: During the American occupation (1945-1952), Western music and culture were heavily promoted. American military radio broadcasts introduced Japanese listeners to a wide range of Western music, including jazz, blues, and classical music.

- Jazz Boom: Jazz became extremely popular in the immediate post-war years, with American jazz musicians performing in Japan and influencing local musicians. Japanese jazz clubs and bands flourished, and jazz was seen as a symbol of modernity and freedom.

Popular Music

- Kayōkyoku (歌謡曲): This genre of Japanese pop music, which had started before the war, became the dominant form of popular music in the post-war period. It blended Western pop melodies with Japanese traditional music. Artists like Hibari Misora became major stars.

- Enka (演歌): Enka music, characterized by its sentimental ballads and themes of nostalgia and loss, gained immense popularity. It appealed to older generations and those nostalgic for pre-war Japan.

1960s-1970s

Rock and Roll and New Genres

- Rock and Roll: Inspired by American and British rock and roll, Japanese rock bands like The Spiders, The Tigers, and The Tempters emerged in the 1960s, leading to the “Group Sounds” (GS) movement.

- Folk and Protest Music: The late 1960s and early 1970s saw the rise of folk music and protest songs, reflecting the global counterculture movement. Artists like Nobuyasu Okabayashi and Takashi Nishioka became prominent.

- City Pop and New Music: In the 1970s, “City Pop” emerged as a genre characterized by its smooth, polished sound and urban themes. Artists like Tatsuro Yamashita and Mariya Takeuchi were influential. “New Music” referred to a broader genre of Japanese pop influenced by Western pop and rock, with artists like Yumi Matsutoya leading the way.

Traditional and Folk Music

- Preservation and Revival: Efforts to preserve traditional music continued, with government support and cultural festivals playing key roles. There was also a folk music revival in the 1970s, with a renewed interest in min’yō (folk songs) and traditional instruments.

1980s

Pop and Idol Culture

- J-Pop Emergence: The 1980s saw the rise of J-Pop (Japanese pop), characterized by its catchy melodies and production. The term “J-Pop” became synonymous with contemporary Japanese popular music.

- Idol Culture: The idol phenomenon began in the 1970s but exploded in the 1980s, with young pop idols like Seiko Matsuda and Akina Nakamori becoming hugely popular. Idol groups, managed by talent agencies, were marketed heavily and had a significant impact on Japanese pop culture.

Electronic and Synth Music

- Technological Advancements: Advances in synthesizers and electronic instruments influenced music production, leading to new sounds and genres. Artists like Yellow Magic Orchestra (YMO) were pioneers in electronic music, blending pop, techno, and traditional Japanese elements.

Key Instruments and Technology

- Western Instruments: Piano, guitar, and other Western instruments became standard in popular music.

- Traditional Instruments: Koto, shamisen, shakuhachi, and taiko drums were used both in traditional music and in fusion genres.

- Synthesizers and Electronic Instruments: The use of synthesizers and electronic instruments became widespread in both pop and experimental music.

Cultural Context

- Economic Growth: Japan’s rapid economic growth in the post-war period led to increased consumer spending on entertainment, including music.

- Media and Technology: The rise of television, radio, and later, the internet, facilitated the dissemination of music. Music programs and variety shows on TV played a significant role in promoting new artists and genres.

- Youth Culture: The emergence of a distinct youth culture influenced by global trends led to the development of new musical movements and genres.

Notable Artists and Groups

- Hibari Misora: An iconic figure in post-war Japanese music, known for her contributions to enka and kayōkyoku.

- The Spiders, The Tigers, The Tempters: Prominent bands in the “Group Sounds” rock movement of the 1960s.

- Yumi Matsutoya: A leading figure in the New Music and City Pop genres.

- Yellow Magic Orchestra (YMO): Pioneers of electronic music and techno-pop in the late 1970s and 1980s.

- Seiko Matsuda and Akina Nakamori: Major pop idols of the 1980s who shaped the idol culture in Japan.

In summary, the post-World War II period was a time of dynamic musical evolution in Japan, characterized by the blending of Western and Japanese elements, the emergence of new genres, and the growth of a vibrant music industry. This era laid the foundation for the diverse and innovative musical landscape that continues to define Japanese music today.

1970s-1990s

The period spanning from the 1970s to the 1990s was a time of significant musical evolution in Japan, marked by the continuation and diversification of existing genres, the emergence of new musical styles, and the impact of global influences. Here’s an overview of Japanese music during this period:

1970s

Rock and Folk Revival

- Folk Music: Folk music continued to thrive, with artists like Happy End blending Western folk influences with Japanese lyrics and melodies. The genre gained popularity for its introspective and socially conscious themes.

- Rock Bands: Rock music expanded with bands like Yellow Magic Orchestra (YMO), a pioneering group in electronic music, and acts such as Carol and RC Succession contributing to the Japanese rock scene.

City Pop and New Music

- City Pop: Emerged as a popular genre characterized by its smooth melodies, sophisticated arrangements, and urban themes. Artists like Tatsuro Yamashita, Mariya Takeuchi, and Anri became influential figures.

- New Music: Continued to evolve, influenced by Western pop and rock, with artists like Yumi Matsutoya (formerly Yuming) gaining prominence for their innovative compositions and poetic lyrics.

Enka and Kayōkyoku

- Enka: Maintained its popularity, particularly among older audiences, with artists like Hibari Misora and Sayuri Ishikawa continuing to dominate the genre.

- Kayōkyoku: Popular music evolved with a blend of Western pop styles and traditional Japanese elements, catering to a broad audience.

1980s

J-Pop and Idol Culture

- J-Pop: Emerged as a distinct genre in the 1980s, characterized by catchy melodies, polished production, and youthful themes. Artists like Seiko Matsuda, Akina Nakamori, and Hikaru Genji contributed to the genre’s popularity.

- Idol Groups: The idol phenomenon expanded, with groups like Onyanko Club and Morning Musume gaining massive fan followings through TV appearances, concerts, and merchandise.

Electronic and Techno-Pop

- Techno-Pop: Yellow Magic Orchestra (YMO) pioneered electronic music in Japan, blending synthesizers, drum machines, and pop melodies. Their influence extended globally and laid the foundation for the techno and dance music scene in Japan.

- Synthpop: Artists like Jun Togawa and P-Model explored experimental and avant-garde synthpop, pushing creative boundaries in electronic music.

Visual Kei and Alternative Rock

- Visual Kei: A subculture emerged featuring elaborate costumes, theatrical makeup, and androgynous aesthetics. Bands like X Japan and Luna Sea combined elements of rock, metal, and glam, gaining a dedicated fanbase.

- Alternative Rock: Bands like The Blue Hearts and Shonen Knife brought punk and indie rock influences to Japan, contributing to a vibrant underground music scene.

1990s

Diversification and Globalization

- Hip Hop and R&B: Japanese artists began experimenting with hip hop and R&B, incorporating local styles and lyrical themes. Acts like Scha Dara Parr and DJ Krush gained popularity.

- Neo-Shibuya-kei: A genre influenced by 1960s pop, lounge music, and electronic sounds, characterized by artists like Pizzicato Five and Cornelius.

- Anime and Game Music: The 1990s saw the rise of anime and game music as distinct genres, with composers like Yoko Kanno and Nobuo Uematsu gaining recognition for their iconic soundtracks.

Pop and Dance Music

- Bubblegum Pop: Mainstream pop continued to evolve with acts like Namie Amuro and SPEED, known for their energetic performances and upbeat tracks.

- Techno and Dance: Dance music gained popularity in clubs and parties, with DJs and producers like Ken Ishii and Takkyu Ishino leading the techno and house music scene.

Traditional and Experimental

- Traditional Music: Efforts to preserve and innovate traditional music continued, with artists like Kodo exploring new interpretations of taiko drumming and other traditional forms.

- Experimental Music: Avant-garde and experimental music scenes thrived, with artists like Merzbow and Otomo Yoshihide pushing boundaries in noise, improvisation, and multimedia art.

Key Instruments and Technology

- Synthesizers and Electronic Instruments: Continued advancements in electronic music technology, including synthesizers, drum machines, and samplers, shaped the sound of many genres.

- Guitars and Drums: Traditional rock instruments remained central in rock, punk, and metal bands.

- Computers and Digital Recording: The adoption of digital recording and computer-based music production allowed for greater creativity and accessibility in music creation.

Cultural Context

- Economic Boom: The economic prosperity of the 1980s and early 1990s supported a flourishing music industry, with increased investment in recording studios, concert venues, and promotion.

- Technological Influence: Rapid advancements in technology, including the internet and digital media, transformed music distribution and consumption.

- Globalization: Increased cultural exchange and globalization influenced Japanese music, with artists and genres gaining international recognition and collaborations becoming more common.

In summary, the period from the 1970s to the 1990s was a dynamic time in Japanese music history, characterized by the diversification of genres, the fusion of traditional and modern elements, and the impact of global influences. This era laid the groundwork for the diverse and innovative musical landscape that continues to evolve in Japan today.

2000s to Present

The period from the 2000s to the present day in Japanese music history has been marked by further diversification, globalization, and the integration of new technologies. This era has seen the continuation of existing genres alongside the rise of new styles influenced by global trends. Here’s an overview of Japanese music from the 2000s to the present:

2000s

J-Pop and Idol Dominance

- Continued Popularity: J-Pop remained a dominant force in Japanese music, with artists like Ayumi Hamasaki, Utada Hikaru, and Kumi Koda achieving commercial success. Idol groups like AKB48 and Morning Musume continued to thrive, utilizing multimedia strategies and fan engagement.

- Visual Kei Revival: Visual Kei bands such as Dir En Grey and Versailles gained international followings, blending rock, metal, and dramatic visuals.

Hip Hop and R&B

- Mainstream Acceptance: Hip hop and R&B genres gained mainstream acceptance, with artists like m-flo, Namie Amuro, and AI incorporating these styles into their music.

- Japanese Hip Hop Scene: Domestic hip hop artists like Kreva, Rip Slyme, and Hikaru Utada (during her collaboration with m-flo) gained popularity, contributing to a vibrant hip hop scene.

Indie and Alternative Scene

- Indie Bands: Indie rock and alternative bands such as Asian Kung-Fu Generation, RADWIMPS, and 9mm Parabellum Bullet gained popularity, attracting a dedicated fanbase.

- Electronic and Experimental Music: Artists like Capsule and Perfume popularized electronic dance music (EDM) and synthpop, blending futuristic sounds with catchy melodies.

2010s

Expansion of Genre Diversity

- Emergence of New Genres: New genres such as “City Pop” revival, characterized by smooth melodies and nostalgic themes, gained popularity among younger audiences.

- Vocaloid and Hatsune Miku: The rise of Vocaloid software and virtual idol Hatsune Miku revolutionized the music industry, enabling fans to create and share their own songs and performances.

Global Influence and Collaboration

- International Recognition: Japanese artists gained international recognition, with acts like BABYMETAL (fusion of metal and idol pop), ONE OK ROCK (rock band), and Kyary Pamyu Pamyu (kawaii pop) touring globally and attracting diverse audiences.

- Collaborations: Collaboration between Japanese and international artists became more common, reflecting global trends in music production and distribution.

Streaming and Digital Platforms

- Shift in Consumption: The rise of streaming platforms like Spotify and Apple Music changed how music was consumed and promoted, providing global access to Japanese music.

- YouTube and Social Media: Artists and labels utilized YouTube and social media platforms to reach international audiences directly, bypassing traditional distribution channels.

Present Day Trends

Diversity and Innovation

- Continued Innovation: Japanese music continues to evolve with innovative fusions of genres, experimentation with new sounds, and cross-cultural collaborations.

- Traditional Influences: Traditional Japanese instruments and musical elements are being creatively integrated into modern compositions across various genres.

Cultural and Social Impact

- Social Commentary: Artists use music to address social issues, mental health, and identity, resonating with diverse audiences.

- Virtual Reality and Live Performances: Virtual reality concerts and live streaming have transformed live performances, offering new ways for fans to experience music.

Global Reach

- International Tours: Japanese artists regularly tour internationally, expanding their fan base and contributing to global music scenes.

- Anime and Game Music: Anime and game soundtracks continue to influence global audiences, with composers like Yoko Kanno and Yoko Shimomura achieving international acclaim.

Key Instruments and Technology

- Digital Production: Advances in digital production tools and software have democratized music creation, enabling artists to produce high-quality music independently.

- Live Performance Technology: Innovations in stage design, lighting, and sound technology enhance the spectacle of live performances, attracting audiences worldwide.

Cultural Context

- Cultural Exchange: Globalization and digital platforms facilitate cultural exchange, influencing Japanese music and allowing it to influence global music trends.

- Youth Culture: Japanese youth continue to shape music trends, with their preferences and creativity driving innovation and diversity in the industry.

In summary, the 2000s to the present day have been characterized by a dynamic and diverse Japanese music scene, where traditional influences meet modern innovations and global trends. From J-Pop and idol culture to indie rock, electronic music, and international collaborations, Japanese music continues to evolve, resonate globally, and influence the broader music landscape.

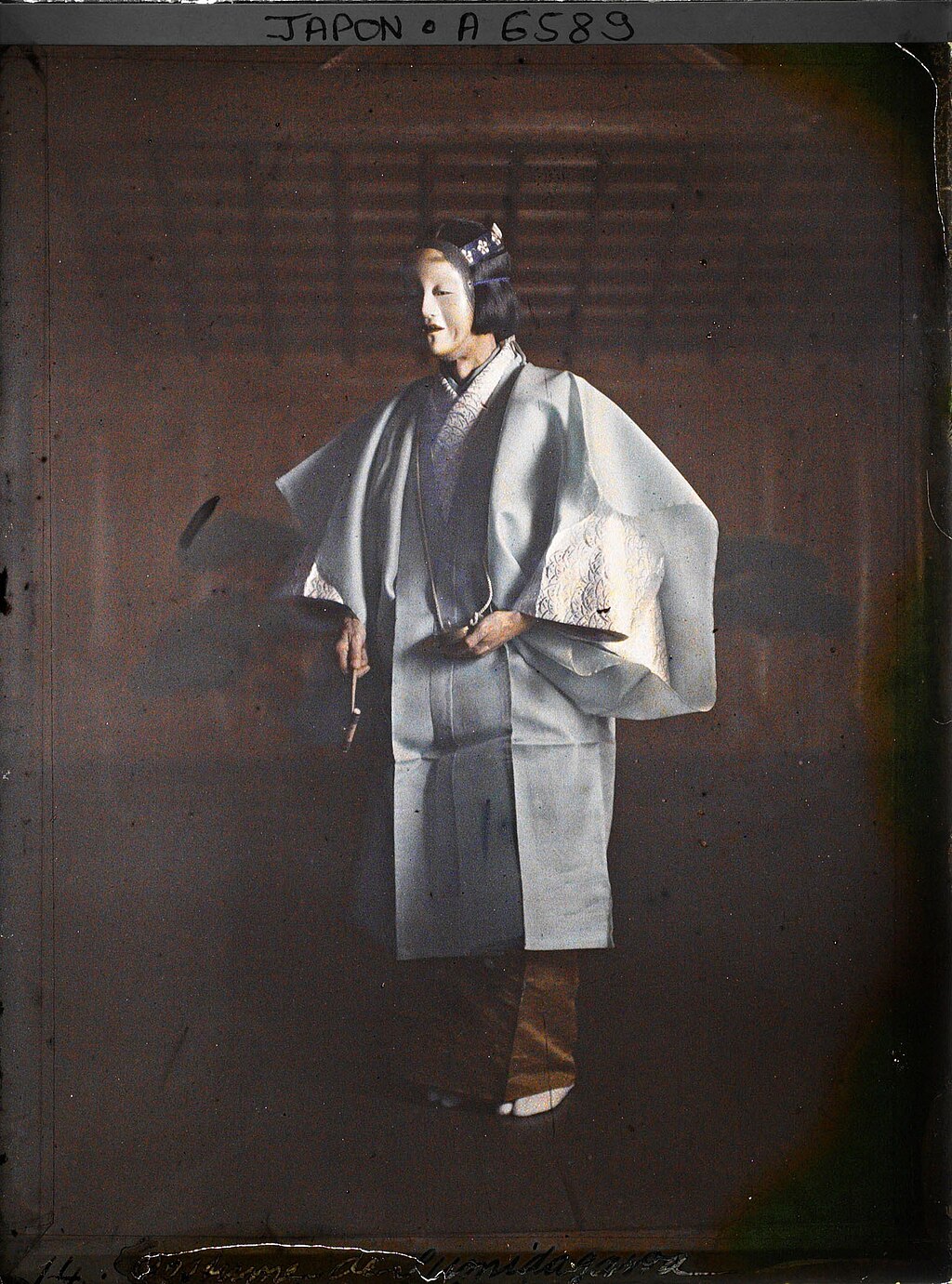

Featured image: Photo by Susann Schuster